Stranger Than Fiction

January 2023

Arthur Conan Doyle and the ‘Frightful Murders at Walworth’

By Dean Jobb

Noises coming from the top-floor flat awakened the residents of No. 16 Manor Place in Walworth, South London early that summer morning in 1860. Philip Beard, a carpenter who lived on the floor below, remembered it as “a sort of rumbling” on the stairwell landing, “like children running about.” Emerging from his rooms to investigate, he heard “a slight scream.” He climbed the staircase in his nightclothes and was confronted with a ghastly sight. A child’s body was lying on the landing. His throat was cut. The bodies of two women were close by, and another young boy was dead in a back room. There was blood everywhere.

Beard scrambled downstairs and rapped on the door of the landlord, James Bevan. “For God’s sake come up stairs,” he cried, “here is murder!”

Before the two men could dress and rush outside to summon the police and a doctor, William Godfrey Youngman appeared on the stairs. The twenty-five-year-old lived on the upper floor with his parents and two younger brothers. His nightshirt was soaked in blood.

“My mother has done all this,” he claimed. “She has murdered my sweetheart and my two little brothers, and, in self-defence, I believe I have murdered her.”

Elizabeth Youngman, forty-six, was one of the slain women. The other was Youngman’s fiancée, Mary Wells Streeter, who had spent the night with the family. His brothers Thomas, eleven, and seven-year-old Charles were also dead. Youngman’s father, a tailor, had left for work shortly before the killings began.

“This is my mother’s doing,” Youngman repeated to Inspector James Dann of P Division of the Metropolitan Police as he was taken into custody. “She came to the bedside where my brother and I were sleeping, killed him, and made a stab at me, and I in my own defence wrenched the knife from her hand and killed her.”

Despite his clumsy attempts to blame his dead mother, Youngman was charged with murder. The weapon used—a blood-covered folding knife—was found among the bodies. The tip and part of the handle were broken off, offering mute testimony to the savagery of the stabbings. It was Youngman’s knife.

The murders both shocked and fascinated Victorian London. “The horror and the apparent purposelessness of the deed roused public excitement and indignation to the highest pitch,” Arthur Conan Doyle wrote of the case four decades later.

Conan Doyle’s interest in crime and criminals extended beyond the fictional mysteries he created for Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson to solve. He also made several forays into writing true crime. In 1901, The Strand Magazine, which had made the author and his detective world-famous, agreed to publish a dozen of Conan Doyle’s tales of real-life crimes.

“The Holocaust of Manor Place,” the first of what turned out to be only three installments, appeared in the magazine’s March 1901 issue. Youngman, in Conan Doyle’s opinion, “was one of the criminals of a century.” What, he wondered, had driven him to slaughter people he should have loved and protected?

“Frightful Murders at Walworth,” screamed a headline when the news broke in the Times of London. Another paper called it “a massacre,” and the neighborhood was reportedly “thrown into a state of feverish excitement.” Large crowds assembled at the murder scene. By one account, people desperate to get inside the blood-stained residence “to satisfy their morbid taste” offered hefty bribes to those standing guard.

As the case moved from coroner’s inquest to trial, a clearer—and disturbing—picture of Youngman and his motives emerged. Streeter, his fiancée, was the daughter of a farmer in Wadhurst, a market town near Tunbridge Wells in the Essex countryside south of London. The courtship had been brief, and Inspector Dann recovered more than a dozen letters Youngman had sent to “My dearest Mary,” signing off as “your ever affectionate lover.” Most of them implored her to buy an insurance policy that would pay £100—about $13,000 today—in the event of her death. When she resisted, he threatened to break off the engagement. When she finally gave in to his demands and agreed to come to London to be married, he urged her to burn the letters.

Youngman was not only a bully, but a liar and a fantasist. He claimed he was “a retired tailor,” even though his last, brief employment had been as a servant and he was unemployed. Quizzed by a friend of the Streeter family, he claimed he was independently wealthy and owned “various places in London.” He told his neighbor, Philip Beard, of vague plans to go “into the farming business.” In his letters, he promised Streeter he had “money enough to supply all your wants and wishes” once they were married. Truth was, he was broke and had been forced to move in with his parents barely a fortnight before the murders.

“So distorted was his outlook,” Conan Doyle concluded in his telling of the tale, “that it even seemed to him that if he wished people to be deceived they must be deceived, and that the weakest device or excuse, if it came from him, would pass unquestioned.”

His insistence that his mother had committed the murders, and he had disarmed and killed her in self-defense, was the most unbelievable of his tall tales. She had disapproved of the impending marriage, but this hardly seemed to be sufficient motive for savagely attacking her own children. There was a history of mental illness in her side of the family—her mother had died in an insane asylum—but if this suggested Elizabeth Youngman had been capable of being a homicidal maniac, it tainted William as a possible lunatic as well. And there was a glaring flaw in his version of events, one that defeated his claim of self-defense; if he was telling the truth, and his mother had wielded the knife, she was no longer a threat once he had disarmed her. Why had he stabbed her four times?

“He never varied from the story which he had probably concocted before the event,” noted Conan Doyle. He exhibited “serene self-belief that the story which he had put forward could not fail eventually to be accepted.”

It wasn’t accepted. When Youngman stood trial at the Old Bailey in August 1860, his lawyer tried to tease out evidence supporting his claim of self-defense. The most bizarre was the suggestion his mother’s illness—she had ovarian cancer—could have made her unstable, and perhaps even homicidal. The disease can make sufferers “very irritable,” a doctor testified, triggering delirium and confusion. “If there has been mania in a family and a disease is acting upon a person, it would be more likely to bring it on.” And homicidal mania in women, the doctor added, often compelled them to “attack those to whom they have the greatest affection.”

Surprisingly, Youngman did not raise the defense of insanity. The attacks on his mother’s sanity would have strengthened his own claim to mental illness. And during the trial his father revealed that his brother had died in a lunatic asylum and his own father had been committed to an asylum two or three times but had died “tolerably sensible.” Youngman’s jailors, however, detected no signs of lunacy or instability, one newspaper reported, other than “the coolness displayed by the man as if nothing had happened to his family.” The London press was convinced he was sane, and a cold-blooded killer. His letters to his fiancée, his actions, his elaborate web of lies—it all seemed too calculated to be the work of a madman. There was not, the city’s Observer noted on the eve of the trial, “the slightest indication of a disordered mind.”

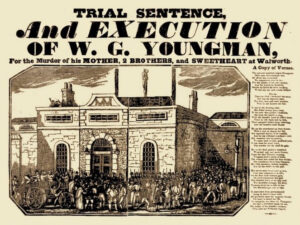

Youngman was convicted and sentenced to hang. An estimated 20,000 people—many of them “the least educated, the most criminal and hardened,” claimed London’s Morning Chronicle—turned out on the morning of September 4 to watch his execution at Horsemonger Lane Gaol. The mob “howled, roared and sang” to pass the time until the condemned man appeared on the scaffold.

Youngman refused to confess and stuck to his story. He had acted in self-defense.

“Do not leave the world with a lie on your lips,” the chaplain urged Youngman as they walked to the scaffold.

“Well,” he replied, “if I wanted to tell a lie I would say that I did it.”

Conan Doyle considered the case “one of the most sanguinary, and also one of the most unaccountable, incidents in English criminal annals.” With every eyewitness dead and no confession of guilt, the case against Youngman rested completely on circumstantial evidence, which “can never be absolutely convincing.” He could not resist repeating, almost verbatim, a line about circumstantial evidence being “a very tricky thing” that he had written for Holmes in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” published in The Strand Magazine almost a decade earlier, in October 1891: “Often a damning chain of evidence may, by some slight change, be made to bear an entirely different interpretation.”

In Youngman’s case, Conan Doyle could find no other interpretation that rang true. “That the man was guilty seems to admit no doubt.”

The more intriguing issue, in the author’s view, was Youngman’s state of mind when he launched his brutal attacks on his defenseless victims. The life-insurance policy he had urged Mary Streeter to purchase was the most damning evidence against him. It provided a motive—greed—and his efforts to have her insured suggested he had planned to kill her; his mother and brothers had been collateral damage. But to Conan Doyle, there was also madness in his methods. Youngman’s “calm assumption” that the insurance company would honor the policy and pay the £100 to someone “who was neither husband nor relative of the deceased” as long as he claimed his mother had been responsible suggested he was either ignorant of business practices or delusional.

Conan Doyle favored the theory that Youngman was insane, especially in light of the revelation that his family “was sodden with lunacy upon both sides.” He believed the case should have been “judged upon medical rather than upon criminal grounds,” with the killer ruled insane and put in an asylum rather than hanged.

There was another lesson to be drawn from the case. Youngman was a killer without a conscience, self-absorbed and oblivious to the harm he caused to others. A psychopath, to use the modern term that was coined barely a decade before Conan Doyle revisited the case in 1901.

“The most dangerous of all types of mind is that of the inordinately selfish man,” the author argued. “His own will and his own interest have blotted out for him the duty which he owes to the community.” The “insanity of selfishness,” as he termed it, that had driven Youngman to commit the horrible crime, was “an evil root from which the most monstrous growths may spring.”

The twentieth century, which had barely begun as Conan Doyle wrote those words, would provide plenty of monstrous, murderous William Youngmans to prove his point.

Dean Jobb’s latest book, The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer (Algonquin Books), won the inaugural CrimeCon Clue Award for True Crime Book of the Year and was longlisted for the American Library Association’s 2022 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Find him at www.deanjobb.com