Stranger Than Fiction

March 2025

The Day They Jailed The Babe

by Dean Jobb

A tall, stocky man in a dove-grey suit arrived at Manhattan’s Traffic Court on a June morning in 1921, and dutifully removed his straw boater when the judge took his place on the bench. There was a stir among the speeders and spectators who filled the courtroom as they recognized the celebrity in their midst. Courthouse staffers gathered at the hallway door, trying to catch a glimpse of him. Some of the onlookers may not have known his full name until a court clerk called his case. He was George Herman Ruth, Jr., but everyone knew him as The Babe.

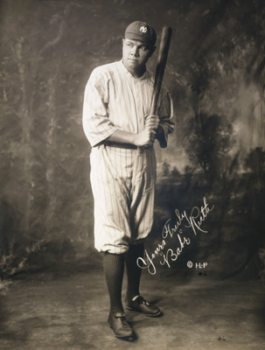

He was the most famous baseball player in the world—one of the most famous people in the world, period. The Sultan of Swat. The Home Run King. “The marvel of the baseball field,” as the New York Evening Mail put it. And that summer the man who wore jersey No. 3 for the New York Yankees was chasing history. Ruth had already set the major league record for home runs slugged in a single season, a mark he was expected to break in 1921. And at age twenty-six, in only his eighth season in the big leagues, he was poised to set a new record for most career home runs.

“I’m sorry to see you back here, Mr. Ruth,” Magistrate Frederick House told him.

Ruth looked nervous, shifting his weight from one foot to the other. Some repeat offenders hauled into traffic court were being locked up for fifteen days. Ruth could not afford to miss a single game, let alone a dozen or more. He was eager to get back to the ball field, to resume his assault on the record books.

House, however, had the power to do something that dozens of major league pitchers had failed to accomplish. He could—temporarily, at least—shut down one of the greatest home-run hitters in the history of baseball.

Nothing in Ruth’s early life suggested he was destined for greatness. Born in Baltimore in 1895, he proved to be more than his parents, who ran a saloon, could handle. He skipped school, hung out on the streets, gulped beer when he father was not looking. At seven he was sent to a reformatory and orphanage, where he trained to be a shirtmaker. One of the Xaverian Brothers who ran the institution, Matthias Boutilier, realized Ruth was a natural on the ball diamond and helped him to develop his powerful swing. His first coach, Ruth would later recall, was “the father I needed.”

In 1914, when he was nineteen, he signed with the Baltimore Orioles, then a minor-league team. Rookies like Ruth who began playing as teenagers were often called Babe—or its Italian equivalent, Bambino—and, in his case, the name stuck.

He broke into the major leagues that summer as a pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. The Sox won the World Series three times between 1915 and 1918 and Ruth set a postseason record that still stands: a fourteen-inning complete-game victory. He pitched nine shutouts in a single season, a record for left-handers that remained unmatched until 1978, and the almost thirty consecutive scoreless innings he pitched in the 1918 World Series was unmatched for more than forty years.

He made an even louder statement at the plate. In the 1919 season he switched to the outfield so he could play every day and get more at-bats. The major-league single-season record was 27 homers, set in 1884 by Ned Williamson of the Chicago White Stockings. Ruth hit 29 that year.

By the time he was traded to the New York Yankees in 1920, Ruth was a slugging phenomenon. He broke his own record in mid-July, on his way to racking up 54 homers. He hit more home runs that year than the entire rosters of all but one of the other fifteen major league teams. It was a superhuman feat. “Nobody can explain him,” said one former teammate. “He just exists.”

Ruth’s size and strength were part of the equation. Six foot two, he weighed more than 200 pounds and his sturdy upper body gave him the power needed to slug homers. A rule change in 1920 helped, ushering in the “live-ball” era—instead of using the same ball throughout a game, umpires could replace them as they became soiled or scuffed, putting fresh balls into play that were brighter, livelier, and easier to see and hit. In 1921, researchers at Columbia University conducted a battery of tests on Ruth to unlock the secrets of his success. The results appeared as a cover story in Popular Science Monthly. Compared to the average person, his eyes and ears were more responsive, his brain sent signals to his muscles faster, and his coordination was “almost perfect.”

At the start of the 1921 season, odds were he would set new records. He was closing in on the career record, which stood at 138. Teammates predicted he would surpass his 1920 tally, perhaps reaching a lofty 75 for the season. “Here’s hoping I am not one of the victims,” joked Philadelphia Athletics pitcher David Keefe. The way “the big fellow” was hitting, said Yankees shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh, “there should be no reason why he should not reach sixty homers.”

Ruth hit his sixteenth home run of 1921 on June 3, putting him one ahead of his pace in 1920. He was the talk of New York. A regular column in the sports pages of the city’s Daily News offered a pitch-by-pitch recap of his latest plate appearances. The Yankees were a couple of games behind the American League-leading Cleveland Indians when they opened a four-game series at home against the reigning World Series champions on June 7. Indians’ pitchers walked Ruth three times, quieting his hot bat, but the Yankees romped to a 9–2 victory.

When the teams took the field the following afternoon, however, the Mighty Babe was missing from the Yankees dugout.

Ruth’s feats on the diamond astounded teammates who knew how he spent his time off the field. Yankee pitcher Waite Hoyt recalled the crowded after-game parties Ruth hosted in his hotel suite, with the bathtub filled with bottled beer on ice in defiance of Prohibition laws. “How did a man drink so much,” asked one of Ruth’s biographers, “and never get drunk?” In the summer of 1920, driving back to New York late at night after a game in Washington, Ruth crashed his car and almost killed himself, his wife, and two teammates. Delaware police concluded the car was traveling at “a fair rate of speed” when it left the road and overturned. Ruth, who gashed his knee, stumbled to a nearby farm to get help. He was disheveled and smelled of liquor. The car, a $10,000 Packard, was a write-off.

In April 1921 a New York motorcycle cop pulled over a maroon, two-seater, bullet-shaped roadster that was traveling north on Broadway at what was then considered the breakneck speed of twenty-seven miles per hour. It was Ruth, on his way to a pregame practice at the Polo Grounds in Washington Heights. “Babe Ruth Is Summoned as a Speeder” was the top page-one headline in the Evening World, eclipsing news of turmoil in postwar Europe. “The home-run marvel drives a car with the same enthusiasm he puts into the swing of a bat,” wisecracked the New-York Tribune. Ruth appeared before Magistrate House on April 27, pleaded guilty, and paid a twenty-five-dollar fine. “I’ll be more careful in future,” he promised.

He wasn’t. On the night of June 2 he was pulled over on Riverside Drive. His speed was clocked at twenty-eight miles an hour and he was ordered to reappear before House.

“The law is made for the high and mighty, as well as the hard-working everyday chauffeur,” the magistrate noted, ominously, after Ruth pleaded guilty. “When a man as prominent as you appears before me, I feel cowardly if I fine him.” Ruth’s failure to show “proper respect for the law” required a stiffer penalty than the loss of a few dollars. He was facing jail time.

“I didn’t realize how fast I was going,” Ruth pleaded. “I don’t want to go to jail.”

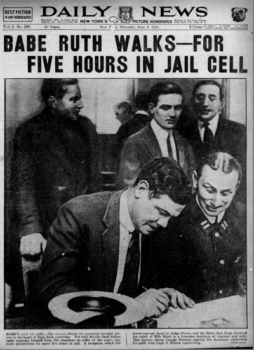

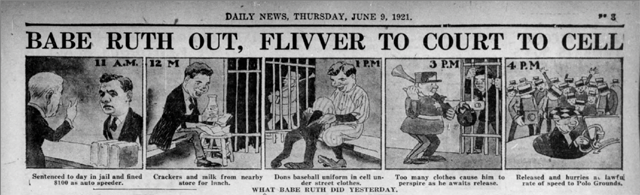

House ordered him to pay a $100 fine and to serve a day in jail.

The highest-paid player in major league baseball produced a hundred-dollar bill—the equivalent of $1,700 today—to cover the fine. He was fingerprinted and put in a cell with several other drivers who had been jailed for speeding. A crowd of almost a thousand gathered outside as he served his time. For lunch, he ordered a box of crackers and bottle of milk from a nearby store. A newspaper photographer climbed a fire escape on a neighboring building, hoping to snap a photo of the traffic court’s famous inmate.

Ruth caught a break. A day in jail for a traffic offense was considered served by four o’clock, when the courthouse closed for the day. The game against Cleveland started at half-past three and he could still make it in time to play a few innings. He arranged for his uniform to be sent downtown from the Yankee clubhouse and he changed into it, then put on his suit over it, to save time once he got to the field.

“I’m going to run like hell to get to the game,” he told one of his cellmates. He had no intention, however, of breaking the speed limit again, at least not in New York. House had threatened to take away his driver’s license if he was caught speeding again, and he would face a longer stint in jail.

“If I’m pinched for speeding again,” Ruth assured his fellow inmate, “it won’t be in this state.”

Ruth was released a few minutes before four o’clock. His roadster was parked behind the courthouse and another magistrate jumped into the passenger seat to ensure he stayed within the speed limit on the nine-mile drive to the ballpark. The game was in the sixth inning, with the Yankees trailing Cleveland by a run, by the time he arrived. The crowd of 20,000 exploded into cheers when he was announced as a pinch hitter. Ruth made little impact at the plate—he drew a walk, then grounded out in the eighth inning—but his return to the lineup seemed to energize his teammates as well as his fans. The Yanks rallied with two runs in the bottom of the ninth for a 4–3 win. “He certainly makes a difference, does the Babe,” observed the New York Herald.

The headlines in the next morning’s papers almost wrote themselves. “Magistrate Scores on Bambino’s Error.” “Traffic Court Judge Benches ‘Babe’ Ruth for Speeding.” “Babe Ruth Walks—Floor of His Cell.”

Ruth went on to break his record that season, belting 59 homers. Had he not lost two or three at-bats while serving time for speeding, he might have made it to 60 that year. Six years passed before he finally hit 60 home runs for a season in 1927, a record that stood until 1961 when another Yankee, Roger Maris, hit 61.

A few hours behind bars, however, did not deter Ruth from committing baseball’s equivalent of a crime. Moments after his sixth-inning walk in his jail-shortened game, he stole second base.

Dean Jobb’s latest book A Gentleman and a Thief: The Daring Jewel Heists of a Jazz Age Rogue (Algonquin Books and HarperCollins Canada) tells the incredible true story of Arthur Barry, who charmed the elite of 1920s New York while planning some of the most brazen jewel thefts in history. It’s a New York Times Editors’ Choice and a Canadian bestseller. Find him at deanjobb.com.

Copyright © 2025 Dean Jobb